The Voysey Inheritance

A fraudulent will case echoes the name of an Edwardian play

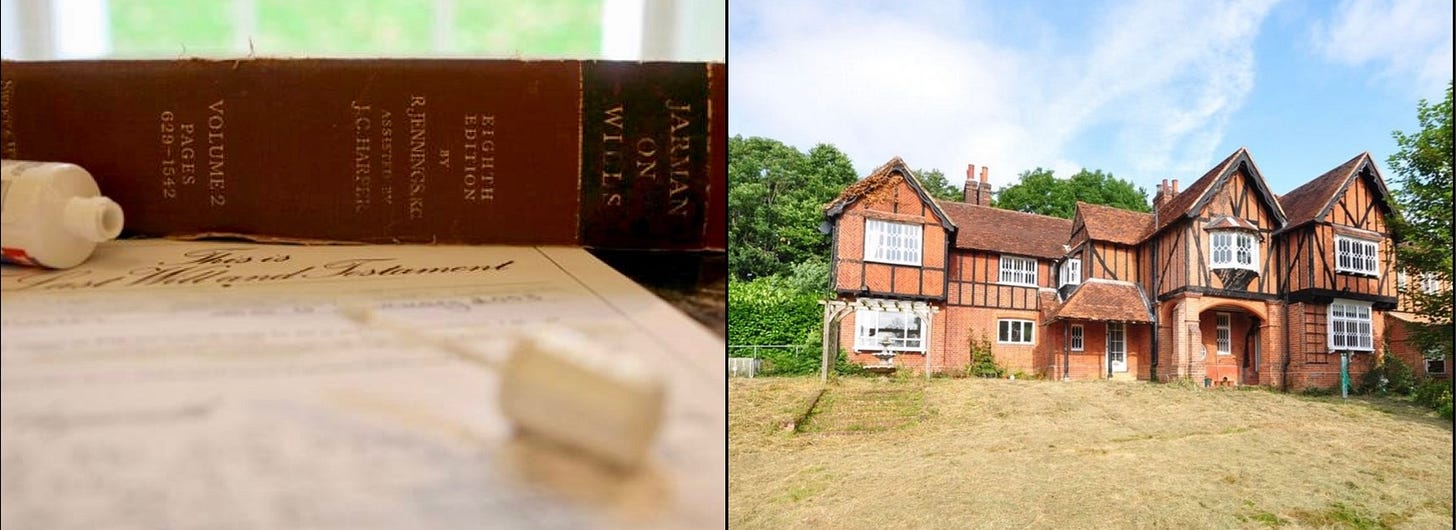

L. A will form and legal textbook on wills, R. Hill House, Much Hadham, Hertfordshire

What memories of early years at school still come to mind in middle age? School lunch, from shepherd’s pie to baked Alaska, to detested beetroot salad with its pickled red juice pooling across the plate like blood at a crime scene. School lunch, school hymns, and prayers. I can still see in my mind’s eye my first primary school class of tiny children in outdoor coats and mittens clasping their hands together and reciting the Lord’s Prayer before going home at the end of the school day.

These long ago memories came to my mind recently as I read about the case of Leigh Voysey, a woman who had in childhood been the head girl of a primary school, and who in late 2024 was imprisoned for attempting to defraud those entitled to the inheritance of her former headmistress’s estate. Whether or not, like me, she had recited “Lead us not into temptation” every day at school in her early childhood, it was a prayer she forgot or ignored after she revisited her former headmistress decades later.

Leigh Voysey’s story – before Mrs Renny’s death

The story begins nearly ten years ago, when Leigh found herself serving lunch to her old headmistress, Mrs Renny, at her home, Hill House in Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, the site of her old school. The Barn had been a small independent primary school which Maureen Renny and her late husband had owned and run in Hill House and its grounds. It had closed when Mrs Renny retired in the late 1990s. Her husband had died not long afterwards, and in 2008 Mrs Renny, then in her early seventies, had returned from another property she owned to live alone at Hill House. She had been in poor and deteriorating health since her husband’s death. From 2014 onwards she needed the help of carers to continue living independently. “Head girl” figures tend to be capable high achievers, but Leigh does not appear to have matched that stereotype. She had worked for Homebase as a retail shop assistant since leaving secondary school in 1997, supplementing her income with shifts for a care agency at a period when she also had a young child to look after.

On 19 February 2016 her care agency sent Leigh to serve lunch to Mrs Renny, the first time they had met since Leigh had left The Barn at the age of 12 in 1991. To serve a carer’s lunch to her old headmistress at her old school must have felt like a curious role reversal. It’s perfectly credible that Mrs Renny may have remembered Leigh, and that this chance meeting prompted some friendly reminiscences of her school days at The Barn. Leigh said she remembered being favoured by Mrs Renny, not only as head girl and class prefect, but by being given the best parts in school plays, and by Mrs Renny taking her side in disagreements with other pupils, and ensuring that Leigh was not in trouble with other teachers when her parents made her late for school. Leigh said she posted to her Facebook account that day about the happy memories that the encounter had brought back.

Leigh’s story of how Mrs Renny later came to make a will leaving everything she had to her begins with this genuine meeting and this plausible conversation, but at each further step her story becomes less and less believable. Leigh said that after 19 February 2016 she visited Mrs Renny once more as a carer, but after that as a friend, about three or four times a year from February 2016 onwards. She said that they would have tea and reminisce about her schooldays. It isn’t entirely implausible that such a first meeting might have prompted further invitations to a former favoured school pupil to visit her ageing former headmistress living alone nearby and in poor health, to offer company and friendly reminiscences. But there was no evidence other than Leigh’s word that any such visits happened. Leigh said that on one of these visits Mrs Renny had previously mentioned an intention to leave her estate to her and asked her to organise two witnesses for this purpose, and to come with them to Hill House some time after 8pm on 12 September 2019. She said that Mrs Renny did not want anyone else to know about this will.

The heart of Leigh’s story about the will was that “everyone that knew Mrs Renny knew how important The Barn School/Hill House and its pupils were to her. I think it was more important to Mrs Renny that she left her estate to me, to save The Barn/Hill House and the surrounding land from development rather than leave her estate to distant blood relatives.... who would sell it, risking that it be developed... she knew that I loved The Barn/Hill House and the land as much as she did and would not sell it off for development.” Leigh said that Mrs Renny had procured a blank will form from a stationer and left it on a table in her lounge. Leigh said she took two friends with her: Amber Collingwood, who was a security officer at Stansted Airport, and a man called Benjamin Mayes. The names and signatures of these two individuals were on the completed document as witnesses to it, and Amber Collingwood’s name and signature were also on it as having signed the will for Mrs Renny because of her poor eyesight. Leigh said that Mrs Renny gave her the completed document to look after. It isn’t entirely implausible that a woman in Mrs Renny’s position might have chosen to leave a keepsake or even a small legacy in a will to someone like Leigh as a mark of gratitude for her visits in her later life. But far less plausible, if not simply incredible, that such a woman would arrange such a clandestine occasion to make such a will in such a way, and having made it, give it to Leigh to keep safe, without even keeping a copy for herself.

Leigh Voysey’s story - after Mrs Renny’s death

Mrs Renny died on 18 January 2020. It was only nearly 18 months later, on 7 June 2021, that Leigh first appeared and claimed that Mrs Renny had made a will on 12 September 2019 leaving her entire estate to her and appointing her as her executor. By this time, Mrs Renny’s estate had been largely completely administered by the executors she had appointed in her genuine last will. Leigh herself had seen that Hill House was on the market for sale with an estate agent in the spring of 2021 and had a meeting with the estate agent and told him that she had a will leaving the property to her. She also wrote to and met Mrs Renny’s solicitor. As the executors of the genuine will had obtained an ordinary grant of probate of that will promptly after her death, Leigh started a claim in the High Court in late 2021 seeking to set that aside and establish the validity as a will of the 2019 document and obtain probate of it instead. She acted as a litigant in person, without legal advice (other than some informal help from a friend’s daughter said to be a former solicitor) which might have dissuaded her from this. Her two witnesses, Amber Collingwood and Benjamin Mayes, wrote letters supporting her claim. Her claim was vigorously defended by Mrs Renny’s beneficiaries, who instructed an experienced KC to act for them. They said that her 2019 document was a complete fabrication, and that even if it was not, there were other reasons why it could not be valid: primarily that after a stroke in mid-2019, Mrs Renny no longer had mental capacity to make a will. And that as the executors of Mrs Renny’s genuine will had already largely administered Mrs Renny’s estate, even if she obtained probate of her 2019 document, Leigh would have no legal right to claim any of the estate back for herself. It was expensive for Mrs Renny’s beneficiaries to instruct specialist lawyers to deal with the civil claim, and very stressful for them.

High Court disputes about the validity of a will, like other civil litigation, involve the filing and exchange of formal “pleadings” of each protagonist’s case and further procedural steps and disclosure and preparation of evidence before an eventual trial. The story told on the face of the pleadings in this case aroused the interest of the media in the spring of 2022, and this publicity in turn led a witness who knew Leigh from her workplace to come forward, and that prompted the police to investigate and the CPS to prosecute not only Leigh, but her two friends who had acted as witnesses. In October 2024 all three were tried on counts of fraud and forgery, and during the course of the trial, all three eventually pleaded guilty, at last acknowledging Leigh’s story of the 2019 document to be a complete fabrication. Leigh’s conviction in the criminal trial enabled the beneficiaries of Mrs Renny’s true will to obtain summary judgment against her in the High Court and uphold the validity of their will without a full civil trial. So it came about that on two consecutive days in December 2024 the High Court gave summary judgment against Leigh and ordered her to pay the beneficiaries’ legal costs, and she was sentenced in St Alban’s Crown Court to six and a half years’ imprisonment for her criminal offences in connection with Mrs Renny’s inheritance. Amber Collingwood and Benjamin Mayes also received prison sentences, and Amber Collingwood was dismissed from her work at Stansted Airport.

The true story of Mrs Renny’s will and inheritance

As it happens, just under a week after the fateful lunch encounter, on 25 February 2016, Mrs Renny made a genuine, valid will with a local solicitor, at the firm’s office. The probate copy of the will shows that she did not sign it herself because her poor eyesight meant that she could no longer read clearly, so it was read over to her and signed at her direction by her solicitor, and her solicitor’s signature was witnessed by a secretary and a trainee solicitor in the solicitors’ office. It contained a range of legacies, many to well known charities. The rest of her estate was divided into 3/10 each for three cousins, and a 1/20 each for the two adult children of her late husband’s son. Mrs Renny was a childless widow, and nothing in this will seems in the least unusual or surprising. Mrs Renny’s solicitor was able to say from her recollection and from her firm’s files that Mrs Renny had long held and consistent wishes about who should inherit her estate, and that the will files contained records of her meticulous deliberations about them. It was also said that she was generally astute and organised with her paperwork and had a “wills” box at home with copies of previous wills in it. It’s entirely unsurprising that a retired headmistress with a “forthright character” should have been meticulous and methodical and used the professional services of a solicitor to make her will. Equally unsurprisingly, she was said to be very fond of her three younger cousins, who were the major beneficiaries of the will.

Hill House, Mrs Renny’s home and the former site of the Barn school, had land around it which Mrs Renny knew was suitable for development and would be of interest to a developer, and valuable if developed. She had made enquiries about it herself. On 25 February 2016 she joked to her solicitor that she would build bungalows for elderly people and move into one herself, but then said more seriously that she would not want the development work going on whilst she was living at Hill House, but would leave that for someone else to worry about.

Mrs Renny had a stroke in July 2019 and her health deteriorated further from then until her death on 18 January 2020. During the autumn of 2019 she had three regular carers in attendance for eight hours a day and she was close to her cousin Gillian who she spoke to every day, and who helped with online shopping and care arrangements even though she didn’t live locally. Neither Gillian nor any of the regular carers ever met Leigh or heard Mrs Renny mention her name, and nor had any of Mrs Renny’s friends and neighbours. The carers knew who these genuine friends and neighbours were and when they visited Mrs Renny. The carers kept a book for visitors to sign in and out of. It had no records of any visits from Leigh. Nor were there any cards or letters or photographs or anything else to show a friendship or connection between Mrs Renny and Leigh, apart from the old Barn school records from Leigh’s childhood, and her sole lunch visit as a carer on 19 February 2016.

Perpetrators of will frauds and their victims

Leigh Voysey’s claim was a meteor-like misfortune for Mrs Renny’s intended beneficiaries. Leigh did not know any of them, or anything about them. She was not motivated by personal spite towards any of them. But the cousins and step-grandchildren knew Mrs Renny and something of her life and her wishes for her estate after her death. This is in marked contrast to another audacious attempt at will fraud perpetrated nearly twenty years ago by a man called Nicholas Doveton (and in which the KC instructed by Mrs Renny’s beneficiaries to defend Leigh’s claim had acted for the Treasury Solicitor as a junior barrister). Doveton claimed to be a distant cousin of a widow called Mrs Janovtchik, who had died in a care home, not only without a will, but without a single known or ascertainable relative entitled to her estate on intestacy, and so her valuable estate passed to the Crown as bona vacantia (an ownerless estate). Doveton initially obtained a grant of probate of a will in his favour which he had forged, but this was later set aside following a trial in which the Treasury Solicitor’s trail of suspicions about it led to the fraudulent deception being painstakingly unravelled. One of the most telling clues was that Mrs Janovtchik’s surname had been misspelled by the doctor who certified her death in the care home, and this unique misspelling, which had no other source, had been replicated by the registrar. Doveton’s replication of it in his forged will exposed his ignorance of and entire lack of prior connection with either Mrs Janovtchik or her late husband.

Leigh Voysey, like Nicholas Doveton, appears to have been motivated purely by opportunism and greed. She lived in the locality and was obviously aware of the development potential of Hill House and its land from local plans and consultations, and she knew that the property was on the market after Mrs Renny’s death. Her case illustrates not just her dishonest greed and her opportunism, but her absolute folly. It is sometimes too readily assumed that people like her and her accomplices, who attempt to defraud others of inheritances, act rationally and with a sophisticated calculation of risk in their crimes. But this is often not the case. From reading the pleadings filed in the civil case and the reports of the High Court’s summary judgment in December 2024, it seems inconceivable that Leigh could ever have persuaded the court that her 2019 document was genuine. As her document, like Mrs Renny’s genuine 2016 will and presumably inspired by it, read as signed, not by Mrs Renny, but by someone on her behalf because of her poor eyesight, there was no hostage to fortune in the form of manuscript text or a signature which might be examined by a handwriting expert and exposed as a possible forgery. But Leigh’s story about Mrs Renny wishing to preserve Hill House from development was both far-fetched and readily contradicted by the solicitor, and in any event did not explain why it would have motivated Mrs Renny to give Leigh not just Hill House, but her entire estate worth over £4M before inheritance tax. Nor was it credible that Mrs Renny could have obtained a blank will form for herself, as by September 2019, she was frail and chair-bound, and relied on her carers and her cousin for all her shopping.

Assuming that Leigh did obtain a copy of Mrs Renny’s genuine will before she created her forgery, she must have either presumed that none of the beneficiaries of it knew Mrs Renny well enough to give evidence about her life and true wishes, or simply not thought that aspect of her case through. On its face, as outlined in the pleadings, the beneficiaries’ evidence, especially that of Mrs Renny’s cousin Gillian, and of Mrs Renny’s regular carers, and of her medical records, and of her solicitor, would have completely ripped apart the threadbare credibility of Leigh’s story at trial. And even if her story of the making of the 2019 will had somehow been believed, she would still have faced a strong case that Mrs Renny by then no longer had mental capacity to make a will. And even if she had won on that issue she would have found it difficult or impossible to take possession of the estate which had already been distributed to Mrs Renny’s intended beneficiaries. Instead, by commencing the High Court case, she set in train a series of self-inflicted disastrous consequences which have included her conviction, her imprisonment, and her prospective bankruptcy and homelessness, as well as separation from her child during her imprisonment. And her child is an innocent victim of her mother’s folly and dishonesty.

In addition to being dishonest, opportunistic and foolish, Leigh was also either entirely insincere in what she said about Mrs Renny’s kindness to her as a schoolgirl and her happy memories of her days at The Barn, or she was callously indifferent to traducing those memories by using them to further her fraudulent claim and attempting to subvert Mrs Renny’s own wishes for her estate. This is also all too frequently characteristic of those who defraud the elderly and dying.

Preventing will fraud

Mrs Renny’s step-grandson, Tom Renny, who is a beneficiary of her estate, has written an intelligent and level-headed short book with an account of his experience of defending Leigh’s civil claim and supporting her criminal prosecution. He and the other beneficiaries deserve every sympathy as victims of this attempted fraud on their inheritance. He makes two suggestions for avoiding the risk of a similar fraud on other innocent victims. One is that there should be a limitation period for people to pursue hostile probate claims against estates which are already in administration under a prior grant of probate. Although there is no fixed limitation period for probate, a modern court will in practice prohibit a claim brought far too late. But this one was unfortunately not late enough for that. His other suggestion is that all wills should be notarised. If anything, the trend in development of the law is in the opposite direction, towards the validation of wills which have not been properly signed and witnessed in accordance with the existing formalities, provided that the intention in them is clear and unquestionable. Such a development would, for example, have validated a will which was the subject of another fairly recent case in which a fraud was revealed at trial. One of the supposed attesting witnesses admitted that the story he and the other witness had told of the occasion on which they witnessed a will made by a professor benefiting another professor, who was an academic colleague and superior of theirs, was untrue. It had been their colleague’s attempt to cover up the mistake of the maker of the home-made will in not arranging to have it witnessed properly in the first place. If only the unfortunately named Professor Whalley had instructed a solicitor to draft and supervise the execution of his will, this debacle could have been avoided.

In Leigh Voysey’s and Mrs Renny’s case justice was served by a criminal investigation, prosecution, trial and conviction being successfully pursued before the further expense and stress of a contested civil trial. This is what should ideally happen in every such case where the evidence points towards forgery and fraud as clearly as it did here.

BARBARA RICH

2 March 2025

Thanks for posting this - very interesting. All the news headlines describing Voysey as head girl of a private school suggest a stereotype of someone confident and successful in life, but that’s very different from the apparent reality. And in any event being head boy or girl of a preparatory school is more like being the milk monitor than the role of head boy or girl in the sixth form of a secondary school.

Voysey and her accomplices are alone responsible for their crimes. But it’s clear from her pleading that other people - both of her parents, and the friend’s daughter who was a former solicitor - knew she was putting forward the 2019 document and claiming it was Mrs Renny’s will. It’s a pity none of them succeeded in talking her out of it (if they even tried to do so) or reported her to the police themselves. The witness who came forward in 2022 and prompted the police investigation to step up did the right thing

Hi Barbara,

What a fantastic article you have written and thank you for the kind words regarding my book! I'm hoping that by sharing my story, I can raise awareness and bring about change to prevent this sort of thing from happening again. I would be more than happy to speak further with you about this case!

Tom Renny