Full Restitution, Empty Promises

The WASPI campaign and increases in women’s state pension age

FULL RESTITUTION, EMPTY PROMISES

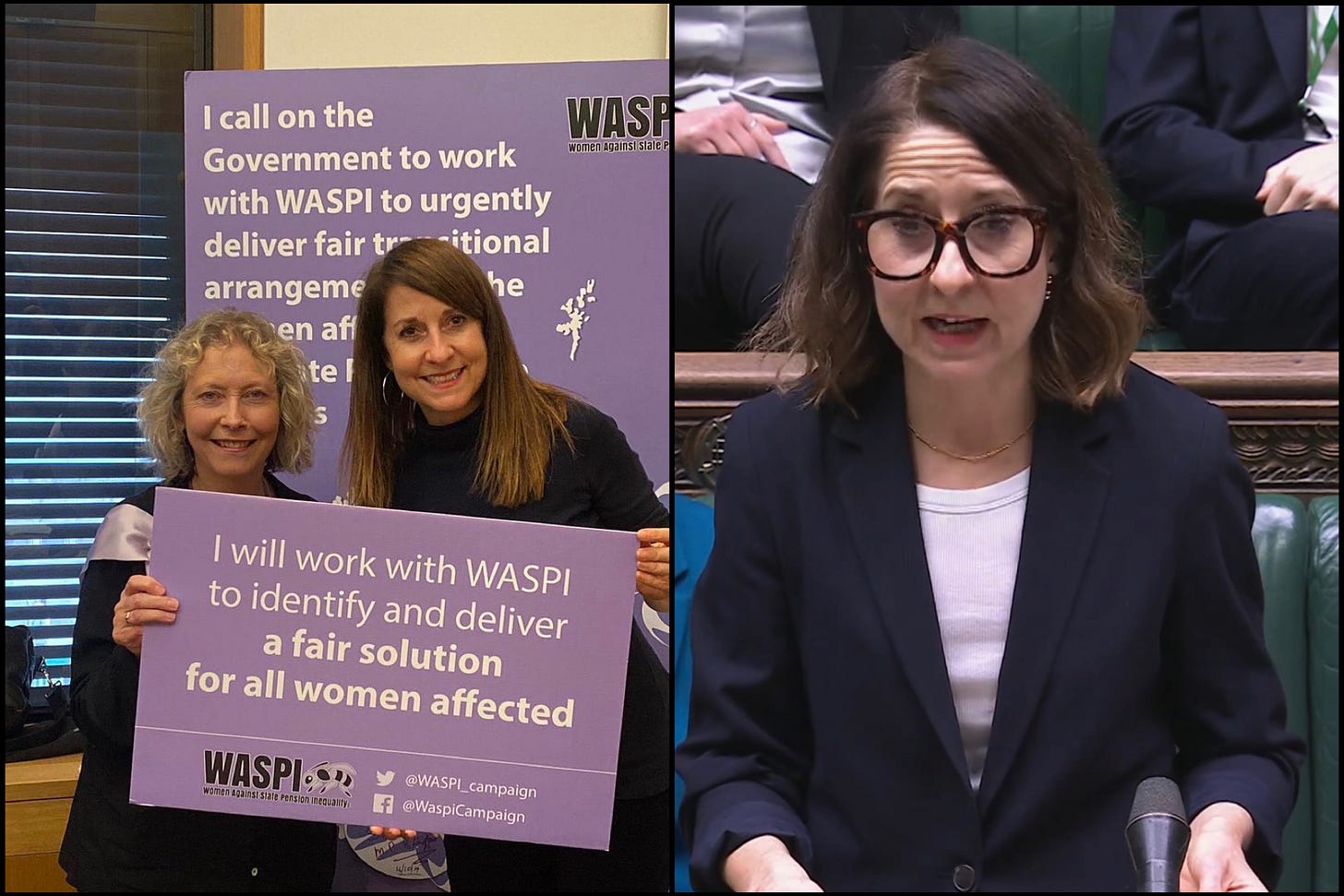

L: Liz Kendall MP with WASPI campaigners in October 2019 R: Liz Kendall as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions making her statement on WASPI compensation in the House of Commons on 17 December 2024

“Women of a certain age” have become increasingly noticeable in their presence as protesters in the UK over the past decade. Some in swimsuits and dryrobes, marching on the headquarters of the local water company bearing a petition and a giant plastic turd to complain about sewage discharges in rivers and on beaches. Some standing outside Crown Courts during criminal trials of other protesters, silently holding placards reminding juries that they have a right to acquit according to conscience. And others dressed up in Suffragette colours and Victorian bonnets to march on Parliament, none more prominently than those of the Women Against State Pension Inequality (“WASPI”) campaign. It’s hard to imagine a previous generation of female protesters, such as the older woman amongst those who protested against nuclear weapons at Greenham Common, or the mothers and older wives of northern miners on strike in the 1980s, doing anything similar, still less engaging a professional public relations agency to amplify it for photographs and headlines in the media.

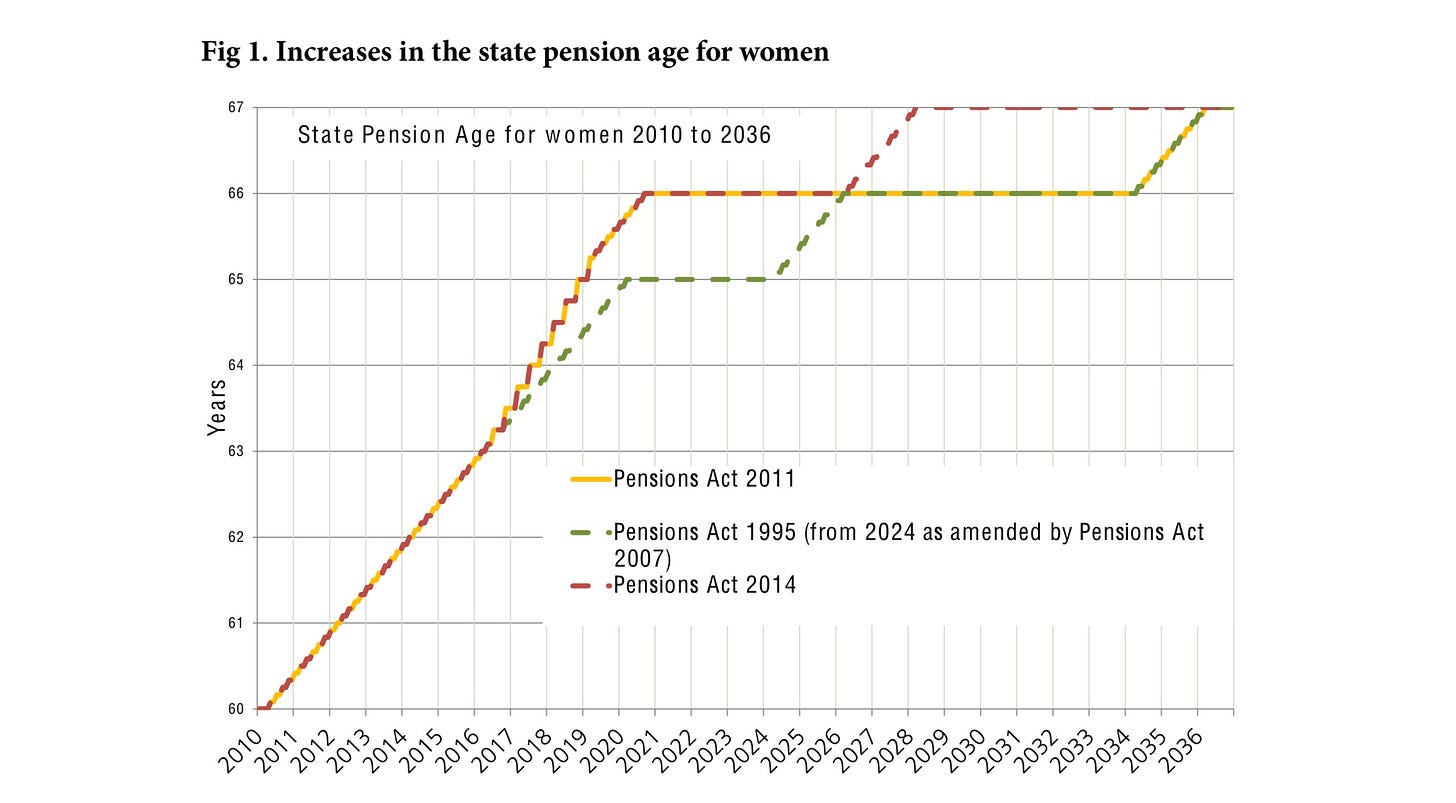

WASPI is a membership organisation which represents numerous women in a large cohort of between 3.5 and 3.8 million who were born between 6 April 1950 and 5 April 1960. The age at which women in this cohort became entitled to receive a state old age pension was equalised with that of men and raised from 60, first to a maximum of 65 and then, as for men, to 66, by a series of Acts of Parliament from the Pensions Act 1995 to the Pensions Act 2011 first taking effect in 2010. These increases in state pension age (“SPA”) for women were made for two primary reasons: to comply with European law on achieving equality between men and women, and to reflect the demographic change of significantly increased longevity since state old age pensions were first introduced in 1948. SPA for both men and women born after 5 April 1960 has continued to rise to reflect this. WASPI has been campaigning since 2015 for some form of compensation for injustices that it claims arise from these changes in SPA and from the way in which women in this cohort found out about them.

Source: House of Commons

Announcement of no compensation for WASPI women

Just over a week before Christmas, on 17 December 2024 Liz Kendall, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, announced to the House of Commons that the government would not pay any compensation to the WASPI cohort. The announcement sparked anger and disappointment from WASPI campaigners and their supporters. There has been talk of a political backlash, including an attempt to force a vote in the House of Commons, and of a judicial review. Much of this anger has been vented against ministers and MPs in the Labour government which took office following the General Election on 4 July 2024, including Liz Kendall herself, as well as the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner, and the Prime Minister, Keir Starmer. All of them had previously made ostentatious gestures of support to the WASPI campaign, consenting to be photographed with campaigners whilst holding pledges to work with WASPI “to identify and deliver a fair solution for all women affected”. These gestures now appear hollow and opportunistic in the light of Liz Kendall’s announcement. She herself had posted her campaigning picture to her Twitter/X account on 16 October 2019, with the message

Women are suffering unacceptable hardship because of changes to their state pension age, with 3000 affected in Leicester West alone. This injustice can’t go on. I was proud to sign the @WASPI_Campaign pledge today to reaffirm my support for their campaign

The WASPI women’s anger in the light of this is understandable and unsurprising.

But I think that at least some responsibility for the disappointment of WASPI members also rests with their campaign leaders. There was always a risk, both legal and political, that their campaign might fail to achieve any practical remedy for women. Were its leaders carried away by their own campaigning zeal, publicity, and success in extracting unenforceable promises from politicians seeking their supporters’ votes in a general election? Or did they fully perceive this risk and manage their supporters’ expectations accordingly? Over a politically unsettled decade, in which both the leadership and strategy of the organisation have changed more than once, how and why did WASPI raise and sustain its members’ expectations for so long?

The dawn of WASPI

WASPI began in March 2015 as a petition to the Department of Work and Pensions (“the DWP”) “to reverse the state pension law”, organised by a single campaigner. She and four others who described themselves as ordinary women personally affected by the changes to SPA then founded WASPI as an organisation and raised money for legal advice through a crowdfunder under the heading “Justice for women born in the 1950s”. WASPI’s original Facebook page said:

“Who are WASPI? We are an action group campaigning against the unfair changes to the State Pension Age imposed on women born on or after 6 April 1951 (and how the changes were implemented). This includes both the 1995 and 2011 Pension Acts.

What is our “ask”? WASPI are asking the government to “Put all women born in the 1950s (on or after 6 April 1951) affected by the changes to the State Pension Age in exactly the same financial position they would have been in if they had been born on or before 5 April 1950”

By December 2015 their campaign had gathered some momentum. At a meeting of the House of Commons Work and Pensions Select Committee on 16 December 2015 (“the WPSC”) two of the organisation’s then leaders, Anne Keen and Lin Phillips, gave evidence. They were complimented by MPs of more than one party on the success of their campaign and its influence on the committee’s decision to look at the process of notification of the changes. The committee chair, the late Frank Field MP said we are not inquiring into … whether the changing of the age was fair to women. What we are inquiring into is whether the process of telling half the population was adequate. Heidi Allen MP then asked the campaigners to give an overview of the campaign and what changes they would hope for. Anne Keen replied we are determined to obtain justice for the lack of notification but immediately went on to complain, not of inadequate notification, but of the wait of up to six years for a state pension. Similarly, Lin Phillips said we are not against equalisation, so we need to dispel that from the beginning. It is just the way it was implemented, the lack of notification … we can prove that most of us have not had any but described the financial loss to women in terms attributable to the SPA increases – Some women have lost up to £40,000, which is a significant change in their lives – rather than to the absence of notification of the change. Heidi Allen responded to this it sounds like it is predominantly about communication, the fact that you just did not know that this was coming. Given that there is not money sloshing around and that that is the world that we are living in now, what would success look like for you? At the end of the year, great job, what is the solution that you are looking for?

Lin Phillips: We need these women to have an income . . . Even though we are told there is no money, we cannot leave women without an income. We are not of a generation that had private pensions, so it is our main income.

Heidi Allen: Is it some solution around income then?

Lin Phillips: Yes, not pensioner benefits and not means-tested. We are all sensible women and, yes, we might have savings, but they are going to be eroded. Six years is a long time to wait.

Anne Keen: Basically, what we are asking – and we feel this is a very fair ask – is for the Government to put all women in their 50s, born on or after 6 April 1951 and affected by the state pension age increases in exactly the same position they would have been in had they been born on or after 5 April 1950. As Lin has touched upon, we have worked since we were 15 and we have built up over 40 years’ worth of National Insurance contributions now. All of our working lives we expected to receive our pension when we were 60. Nobody told us any different. Although there was not a written contract as such, there was a psychological contract.

I have quoted these questions and answers so fully because they set the scene for WASPI’s campaign (which has subsequently recognised that its cohort’s earliest birthdate is 6 April 1950, not 1951). They make it clear that WASPI’s then leaders were being told by MPs even then that any remedy would be compensation for failure to give adequate notice of the changes, not for the increases in qualifying age, but that the campaigners were nevertheless seeking more or less full restitution of the value of the pensions that would have been paid at 60 if the increases had not taken effect at all. Lin Phillips’s phrase “a psychological contract” accurately describes the underlying expectations.

In pursuit of legal remedies: the Parliamentary and Health Services Ombudsman and maladministration

WASPI launched a crowdfunder in 2016 headed “Fair State Pensions for WASPI Women”. It rapidly raised £100,000. Its purpose was to explore two potential routes to a legal remedy for women affected by the changes to state pension age:

- a judicial review challenge to the legality of the changes themselves, and

- maladministration complaints about the inadequate way in which the DWP had communicated the changes to the women affected.

It is clear from the published updates to the crowdfunder website that, no doubt on legal advice, WASPI did not pursue a judicial review of the legislation. That decision marked the end of any route led by WASPI towards full restitution for the cohort as a remedy which might conceivably be directed by a court order following a successful judicial review. From 2017 onwards WASPI focused on pursuing complaints of maladministration to the Parliamentary and Health Services Ombudsman (“the PHSO”). The PHSO is an official whose role is to independently investigate and report on complaints that have not been resolved by government departments. Maladministration essentially means “administrative incompetence” and can exist even where there is no legal remedy enforceable by the courts for the same activity, or neglect of activity complained of.

The gist of the WASPI complaints was that the DWP had failed to notify women affected by the change in sufficient time to make orderly plans for a later retirement without undue financial hardship. WASPI encouraged its members to pursue complaints to the PHSO. Their website said

We want to cause such a high volume that it will further compel the Government to look in earnest at making remedy for the “grotesque disadvantage” and financial loss we have suffered

The WASPI complainants prompted the most extensive investigation the PHSO had ever taken. Reading through past decisions of the PHSO on complaints made by single individuals, it is clear how exceptional the WASPI women’s complaint was. WASPI and its solicitors prepared detailed guidance and template letters for supporters to use to submit complaints. The wording of the template letter encouraged women to claim compensation based on the amount of pension they would have received if they had been eligible at 60, together with other loss such as interest on savings used for maintenance instead. Under the heading “Remedies”, the template letter read

[I consider that any financial payment should reflect, at least, the amount I would have received, had I received my SPA from the age I had understood it would be paid until the date I became entitled under the new SPA]

[EXPLAIN ANY FURTHER LOSSES]

One woman asked on Facebook for help in completing her letter

Just about finished my letter but having problems finding out how much I have lost financially dob Jan 54, any ideas where I can find the info? thanks

The reply, posted by WASPI, read

The amount of pension you lost per week x by the number of weeks it’s delayed and take into account anything else you might have lost eg interest on savings if you’re living on those. For those who have had to sell homes and downsize then fees incurred with that.

So although WASPI recognised that in pursuing their maladministration claim, their “ask” for their supporters was for compensation for failure to give adequate notification of the change to individuals affected by it, they continued to encourage their supporters to claim compensation at the same level they might have expected if the increase to their state pension age had not taken effect, or had been reversed. This was effectively encouraging WASPI women to seek full restitution in all but name.

But a remedy for maladministration could never have offered any women in the WASPI cohort full restitution. The definition of maladministration and its impact on individuals, together with the PHSO’s own severity of injustice scale , divided into six levels of injustice with recommended financial compensation ranging from £0 to £12,500 or more, makes this obvious to any attentive reader.

The PHSO’s investigation resulted in two reports: stage one (finding of maladministration) published on 19 July 2021, and stages two and three (injustice and remedy) based on investigation of six sample cases on 21 March 2024. The PHSO’s findings on maladministration were relatively narrow, establishing a period of 28 months between December 2006 and April 2009 during which the DWP failed to make adequate progress with the task of informing women individually of their SPA increase, a task which it had decided was necessary. WASPI successfully challenged the PHSO’s findings on injustice and remedy as set out in an unpublished final version of its report in December 2022 in a judicial review application which was compromised prior to hearing. In its published final stage two and three report the PHSO found that maladministration in DWP’s communication about the Pensions Act 1995

Resulted in complainants losing opportunities to make informed decisions about some things and to do some things differently, and diminished their sense of personal autonomy and financial control. We do not find that it resulted in them suffering direct financial loss

The PHSO asked Parliament to identify a mechanism for providing appropriate remedy to those who had suffered injustice, setting out its view of what it would consider an appropriate remedy. This was financial compensation of up to £2,950 for each woman affected, or level 4 on the PHSO’s published scale.

In pursuit of legal remedies: judicial review

WASPI’s leaders are not responsible for, and had nothing to do with the decision to seek full restitution in a judicial review. This was pursued by Backto60, a separate organisation which broke away from WASPI, and which supported two individual litigants (one of whom had to acknowledge in her evidence that she had in fact been notified of the increase in her SPA by her occupational pension provider). Backto60’s unsuccessful judicial review in 2019 and equally unsuccessful appeal to the Court of Appeal in 2020 achieved nothing other than to put beyond any doubt that the increases to SPA were lawfully made and not vitiated by any form of age or sex discrimination, and that the government had no legal duty to notify women of them. Indeed, the Court of Appeal made it clear that even if any of the grounds had been upheld, the long delay since 1995 would have made it almost impossible to fashion any practical remedy. The claimants’ lawyers did not even ask the court to order any specific practical remedy, let alone full restitution. Backto60 seriously misled its followers about this, crowdfunding for the litigation on an insistent slogan of confidence in achieving full restitution, which its leaders must or should have known was impossible.

The split between WASPI and Backto60 over the judicial review and appeal disadvantaged the entire cohort. It delayed the PHSO’s investigation, as such investigations cannot proceed concurrently with pursuit of a legal remedy in the courts, and was unhelpful to WASPI and its supporters in that respect. And as WASPI had no responsibility for the case, they did not need to “own” it, or explain its failure to their supporters. But its failure still had implications for the entire cohort of women.

In pursuit of legal remedies: CEDAW

CEDAW is the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, a UN treaty to which the UK is a party. In the Backto60 judicial review proceedings the court said that reference to it added nothing to the claimants’ case. CEDAWinLAW is a successor organisation to Backto60. In 2021 it organised a “People’s Tribunal” resulting in a report produced by a retired Australian judge, Jocelynne Scutt AO, which purports to find that the government has discriminated against women in the WASPI cohort, and resurrects the hope of full restitution for them. But a “People’s Tribunal” is an entirely informal process and its outcome has no bearing on English legal proceedings at all. Despite this, and despite the finality of outcome of the Backto60 judicial review, in 2022-23 CEDAWinLAW crowdfunded a further c£38,000, commenced, and then withdrew further judicial review proceedings against the DWP. It used, and continues to use, presumably with their consent, the names of a number of lawyers, in support of its continuing campaign for full restitution, apparently to be achieved via a process of proposed mediation with Liz Kendall. It is difficult to see what possible legal claim there for it to litigate or attempt to mediate, and no minister is prepared to meet with the group in the absence of active litigation. CEDAWinLAW’s current “ask” for full restitution has neither legal nor political credibility.

Towards the denial of compensation

After the PHSO’s final report was published in March 2024, WASPI changed the wording of their “ask” to read as follows on their website:

Fair and fast compensation for all women affected by the lack of notice regarding the State Pension age increases (1995 and 2011 Pensions Acts) to reflect their financial losses, the sustained damage to their mental health and well-being and the additional impacts. We also call for the Government to act on the PHSO findings now to prevent any longer-term damage to WASPI women

At the meeting of the WPSC on 7 May 2024, WASPI’s current leaders were asked for their response to the PHSO proposal. Angela Madden, WASPI’s Chair, said

We have never campaigned for anything other than some compensation for what we saw as the failure of the Department of Work and Pensions. So, we are pleased with the report. It has identified that there was maladministration – big tick for us. It has identified that the remedy should be compensation – big tick for us. It has also laid the report before Parliament, which we are really happy with because we think that Parliament is the right place for that decision to be made. The level [of compensation] suggested in the report, we think, is on the low side.

This view was echoed by Rebecca Long-Bailey MP, co-chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on State Pension Inequality for Women, saying As Angela has said, the proposals, or recommendations shall we say, in the report for a level 4 injustice scale compensation scheme are very low, given the amount of evidence that we have certainly received as an APPG and the extreme levels of injustice that many of the women that have expressed their situations to us have faced.

A little further in the course of the meeting there was a revealing exchange in questions from Dr Ben Spencer MP. He said I have people contacting me who believe that as a consequence of the Ombudsman’s decision, they are likely to or could get full reinstatement of the pension, which obviously is something very, very different. I don’t think for a second it is their fault for believing that. There is a lot of miscommunication in something that is so important and so emotive. What are your reflections in terms of the communication that is happening at the moment around the stages of the case and making sure that people who are affected know the situation and know what potential things could happen in the future?

Jane Cowley, WASPI’s campaign manager, replied, but appeared to have misunderstood the question, as her reply was about the DWP’s failure to inform women of changes. Dr Ben Spencer then said

Perhaps I did not communicate my question properly. Right now it strikes me, because this is a fiendishly complicated area, that there is a danger of many people misunderstanding exactly what the ombudsman’s decision was, the scope of it, and the potential changes going forwards. Particularly around the fact that it was a very narrow decision that the ombudsman made about maladministration regarding communication rather than the policy itself. When you look at the compensation… full restitution isn’t part of that. I am a bit concerned that, with the focus of what is happening on the case, some people will misunderstand what the implications will mean for them going forwards, if that makes sense.

Angela Madden replied to this

It was never our campaign to go for restitution; we have always campaigned for compensation. There are some campaigners for restitution expecting to get their full pension back. We feel that there are many more campaigners who are willing to accept that compensation is the right way forward. Full restitution would be a fair remedy if the Government had broken the law; that has already been decided in court.

We have tried throughout the course of our campaign, to communicate and manage the expectations of women. We have a large following on social media. We have got members; we have got a website. Our reach is probably hundreds and thousands of women and they do expect compensation. But they expect compensation to match the injustice they have suffered. I think if it does, they will be satisfied. If it doesn’t, then they won’t. I think that the level of compensation commensurate to the maladministration is a bit off.

I am sceptical about these claims of appropriate management of women’s expectations. You do not have to look far on social media even now to find women claiming that they are entitled to be compensated to the extent of five or six years of pension payments and complaining that the Ombudsman offered a measly £3,000. One woman whose story was reported by the BBC following the PHSO’s report in March complained that she had to spend £20,000 by taking a big chunk of money out of a private pension pot to retrain in healthcare, including reiki, to make some income until she turned 66. She is dissatisfied with the level of compensation proposed by the PSHO because I don’t want compensation, I want the money you have stolen from me. This reflects both a misunderstanding of compensation for maladministration and a widely held mistaken belief that a state pension is a personal fund purchased by national insurance contributions, not a contributory welfare benefit with a value (if compared with the cost of purchasing an equivalent annuity on the market) greater than many individuals’ lifetime NI contributions, and paid for out of the current national insurance contributions of men and women who have not yet reached retirement age.

As the record shows, WASPI has from the outset of its campaign encouraged its to members hope for restitution for the perceived injustice of the increases to their SPA, even if labelled as compensation for maladministration. I think that this explains some of the leaders’ dissatisfaction with the level of compensation suggested by the PHSO. I also think that there were a number of signals leading to the government’s decision not to pay compensation which WASPI’s leaders appear either missed, discounted, or failed to reflect in their campaigning or their communications with their supporters.

(1) The failure of the Backto60 judicial review and appeal, and the refusal of the UK Supreme Court to grant permission for any further, final appeal. The absence of any court-based legal remedy inevitably weakened WASPI’s negotiating position with any government seriously considering compensation for the entire cohort.

(2) WASPI’s resistance to means testing and to stringency in merits testing for individual claims to compensation, and to the level of compensation recommended by the PHSO. Unless either means or merits tests or both were introduced into a process for assessing compensation to be paid to individuals, it was obvious that there would be windfall recipients amongst those who were well off or well informed, or both, and understandable that there would be both government and public resistance to this. To ask for compensation for the entire WASPI cohort, without either means or merits testing, coupled with the inexorable arithmetic of its sheer size, means asking for a minimum of £3.5 billion, and potentially a great deal more, to be funded by a younger, less well off generation of working people whose future state pension age is even higher than 66. Any government might have said “no” to this, on the grounds that it was disproportionate and unaffordable. It is fanciful to imagine that the previous government would have said “yes” if it had continued in office, or been re-elected. An uncosted promise of £58 billion in the Labour manifesto for the 2019 general election, under its previous leadership, sank without trace when the party was defeated at the election in December 2019.

(3) One shrewd and apolitical commentator grasped these political realities immediately after the PHSO’s March 2024 report was published. Jill Rutter’s Institute for Government blog pointed out that the PHSO outcome risked satisfying no-one, at considerable cost, and suggested that perhaps the best outcome would be for the government to learn the lessons and move on without paying compensation, but invest a fraction of in increasing women’s financial literacy and ability to plan for their retirement. Did WASPI’s leaders read and reflect on this?

(4) In railing against politicians now in government WASPI have overlooked that their smiling pledges of support were never made with the seriousness or specificity of a manifesto commitment. A month before the General Election, on 4 June 2024, Rachel Reeves told journalists in Edinburgh that she recognised the injustice to the WASPI women but that Labour would not put forward anything in its manifesto that was not fully costed and that she had not set out any money for WASPI compensation. Were WASPI’s leaders paying attention to this?

(5) Last but not least, WASPI’s leaders might have foreseen and forewarned their members of the Government’s own reasoning in its published response to the PHSO’s March 2024 report: that the DWP’s own research showed a high level of relevant awareness of future changes to SPA, and that the PHSO’s reasoning on injustice was flawed in assuming the effectiveness that sending unsolicited letters earlier would have had. The PSHO’s statement in response to this is here.

Conclusion

The changes to state pension age affecting 1950s women were made for demographic and other reasons which continue to be relevant, and were democratically made by primary legislation. People have to live with the consequences of these decisions. The government had no legal obligation to notify women individually of the increases, although when it did decide that it should do so, it failed to do so with administrative competence for a period of 28 months and this caused some injustice to women affected.

I am sympathetic to the genuine hardship experienced by some women who made decisions they would not have made if they had known of their later state pension age date, or who were unable to continue to work until that later date through incapacity or having to take on caring responsibilities, or some other good reason. I think these hardships should have been more promptly alleviated by means tested working age benefits. But not all the stories of WASPI women are stories of genuine hardship, and it is difficult to feel sympathy for those who had the choices open to the relatively affluent, who were members of public or private sector defined benefit occupational pension schemes (eg in the NHS, civil service, local government, teaching in state or independent schools, colleges and universities, or working for larger retailers, banks and financial services, or airlines, to take examples of occupations with a significant female workforce in that generation of women), or those who took a decision to retire (in some cases well before the age of 60) and drew up financial plans simply assuming without checking that their state pension age was 60. I am sceptical of some of the claims not to have been aware of the change over the long lead-in period from 1995-2010, and unsympathetic to those who made decisions about retirement without checking when their state pension would be paid. I think that comparisons made by some WASPI supporters to the victims of the infected blood scandal or the Post Office wrongful prosecutions, or Grenfell, are absurd to the point of insult to the victims of those tragedies. Clerical maladministration which has not even caused direct financial loss to its victims is simply incommensurable with loss of life, loss of livelihood and reputation, or wrongful conviction and imprisonment.

And I think that WASPI’s leaders and supporters should reflect on whether a campaign which unequivocally abandoned the pursuit of full restitution even as compensation for inadequate notification, and which asked for less money for fewer women would have been more successful in achieving something for some of the women in the cohort. As it is, the campaign leaves an uncomfortable impression that whilst they borrowed the colours of the Suffragettes and pursued a legal or political objective, their fervour and rhetoric were closer to that of a 19th century religious movement, complete with its own songs of praise in the form of the “WASPI anthem”. And like such religious movements, it promoted a belief which resisted doubt, denial and dissent until it was too late, and it shattered irretrievably under the weight of reality.

Barbara Rich

31 December 2024

“We are WASPI, here’s our story

We will tell it through the land

As we stand to fight for justice

Together hand in hand

We are women of the 50s

From near and far we come

Campaigning to get justice

We won’t stop until it’s done

We are WASPI

We want justice

Come and join us in our fight

United we are standing

We strive to claim our right

We were told we’d have our pensions

More than 40 years ago

So we worked and slogged and toiled

More than you’d ever know

We paid into this country

We always gave our best

In belief we could reclaim it

But still there is no rest

We are WASPI

We want justice

Come and join us in our fight

United we are standing

We strive to claim our right

And now that we are sixty

They have gone and changed the goal

The country we paid into

Now destroys our heart and soul

The Government has failed us

Now our pensions are denied

They did not give us notice

They tried to take our pride

Generations come together

Each corner of the land

With our voices raised in union

United we will stand

We will shout until they hear us

We never will give in

Then when we win the victory

Our retirement will begin

We are WASPI

We want justice

Come and join us in our fight

United we are standing

We strive to claim our right

Thank you for this admirably clear explanation. I find the entire WASPI campaign selfish and entitled and deliberately misleading, to the detriment of some of the women themselves but also to claims for equality for women. The fact that so many politicians jumped on this bandwagon rather than speak clearly about why their claims were unjustified is a depressing coda to this story. The fact that the right decision is, even now, being justified because there is insufficient money rather than because the claim itself is unjustified, does not help. It takes a peculiar sort of talent to damage trust in politicians even when taking the right decision.

Financial literacy and education is something which needs far more focus than it ever gets.

I am co-founder of the Protest Against the 2011 SPA Acceleration face book group which we founded in December 2010 when we heard of the proposed law. It was unfair and badly worked out, in that 1950s women just slightly younger than others had years more added to their SPA. It affected men too, as both women and men's SPA went up on a rolling scale to 66. Along with Unions Together, AGE UK and Rachel Reeves, we achieved up to 6 months concession for the worst affected. We failed to stop the acceleration altogether as the Coalition government voted that concession through and outnumbered Labour MPs who voted against it. It was a great pity, as if we had stopped that unfair law, both women and men's SPA would have been at up to 65, not 66. We have said all along, other groups asked too much and got nothing! As it became too late to stop the 2011 we are now a friendship, information and support group.